On Monday, after class, I went to the British Museum for a few hours. While I was surrounded by the pieces of history that I never believed I would get the chance to see, I began wondering something. Are these pieces for us to view? Were we, as humans, supposed to see these items two, three, four, five, ten thousand years later? Who are they for?

A wall painting from the tomb-chapel of Nebamun, dating 1350 BC.Yesterday, I saw Egyptian mummies, Grecian pots, Roman busts, Babylonian coins, and countless other artifacts that at one point, were an important piece of someone’s life, if not their entire life.

Due to the long period of imperialism that Britain went throughout history, hundreds of thousands of artifacts from civilizations across the globe have made their way to Britain. A very good portion of them have ended up in the British Museum.

Monday, I spent most of my time in the Ancient Egypt exhibit. I wandered around the pieces left of The Book of the Dead, and many mummies, artifacts, and other pieces of that civilization’s history. I almost became overwhelmed at the amount of history that surrounded me. As someone who wants to work in museums and be hands on with history as a career, I wasn’t sure exactly what to feel. It had been a long time since I had been at a major museum like the British Museum, so I was really shocked by the pieces of history that surrounded me. Not to mention, the history museums that we have in America don’t have artifacts dating back nearly as far as some of the things I saw yesterday.

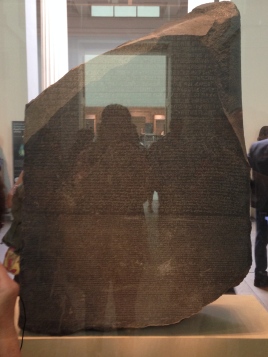

The Rosetta Stone, found in 1799, contains a decree inscribed in in 196 BC, and includes Egyptian hieroglyphs, Demotic text, and Ancient Greek. This provided us with a way to interpret ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs.

When I was in the Ancient Egypt exhibit, I began to wonder, would the people who prepared these artifacts or mummified these people, or even the people within the binds of the mummies on display, would they want their work (or their bodies) to be placed behind glass for viewing? While most of the pieces that I saw on Monday were obtained illegally during imperialistic journeys (or just straight up stolen from civilizations), not all of them were. Some were excavated from actual archeological digs.

But that still doesn’t answer the question: does the significance of these items cancel out the fact that they were once an important part of someone’s life?

As someone who hopes to work with these items, I feel torn. I do believe that the current significance of the artifacts are so great that they should be preserved, cared for, and displayed in such a way that will honor them. (Especially artifacts such as mummies and skeletons, that were once human beings like you and me.)

Since I feel as if I have a slight bias on the subject, I am genuinely curious as to what other people think. Please feel free to start a conversation about this, whether it’s in the comments of this post, by sharing this post with your friends and family on Facebook or Twitter, with me (see the contact me tab), or just with people at home.

lydia.

[J] Well in most cases we don’t have the consent – explicit or implied – to preserve, view, display, copy etc items made owned or authored by persons now deceased. But here’s the dilemma: Consdier an historical artifact that is discovered (as in an archaeological dig) or comes into our possession (by inheritance, for example). We conclude we don’t have authority to preserve, view, display, copy,etc (let alone commercialize), what do we do? We might disown the artifact in principle, but what does that mean in practice? Do we give it away, sell it and give the money to charity … or burn it, destroy it, ceremoniously send it out to sea on a burning raft – or just simply chuck it in the refuse bin? In the case of intellectual artefacts (for example, the understanding of ancient cuniform scripts) do we set about a process – that might take many generations – of extirpating that knowledge from the body of human wisdom. Why would we think we have a mandate to do any of those things? No, I believe we are right to show respect to the creations and debris of the past by searching to understand their significance and value in the historical context, and – an even higher plane of respect – to find ways of making those historical artefacts of value and significance and maybe even utility in our current age. Museums, and related institutions, are curators of the human spirit.

I absolutely agree with you! We are right to put it on display in a way that respects civilizations and cultures of the past, as well as study them to learn more about our past.

[D] Be sure and to to the V&A!

Some really interesting points here.

I am much more concerned with the proper ownership of the artifacts than respecting the wishes of the dead. Artifacts stolen from a country without permission or from a culture to which they are still significant is wrong, and with modern technologies–photography, video, and highly realistic modeling– I don’t think it’s necessary or ethical to remove them. However, objects obtained legally and with permission for the purpose of education, regardless of how their original owner might have felt thousands of years ago, I would argue we are obligated to make available to the public.

I agree totally. Without the information learned from artifacts such as those in the British Museum, we wouldn’t have the information about many cultures that we do today.